Every boardroom I sit in right now is obsessed with the same question: How fast can we adopt AI? But adopting AI is just an input, not an outcome.

Take engineering as an example. Leaders are spinning up pilots, funding copilots for developers, and greenlighting new AI-powered applications at a dizzying pace. If you judge by the number of launches and dashboards alone, you’d think many enterprises are well on their way to becoming “AI-first”.

AI is accelerating how fast you ship. But running what you’ve shipped still depends on humans.

So, if your AI strategy works — if you actually succeed in getting dozens or hundreds of applications into production using AI — you’re going to hit a brutal constraint: your people can’t run what you’ve built.

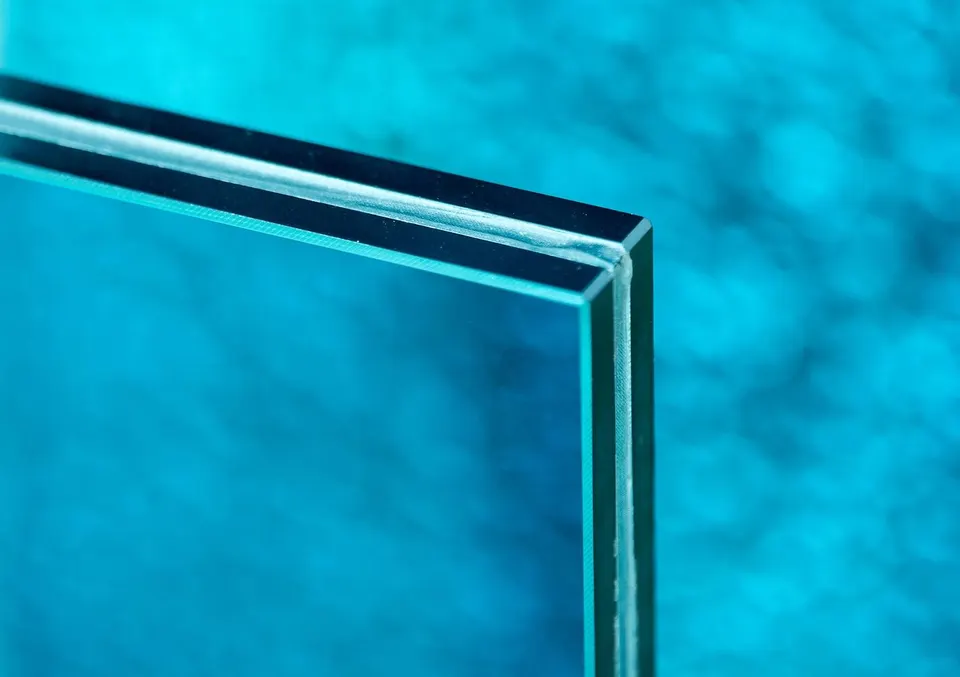

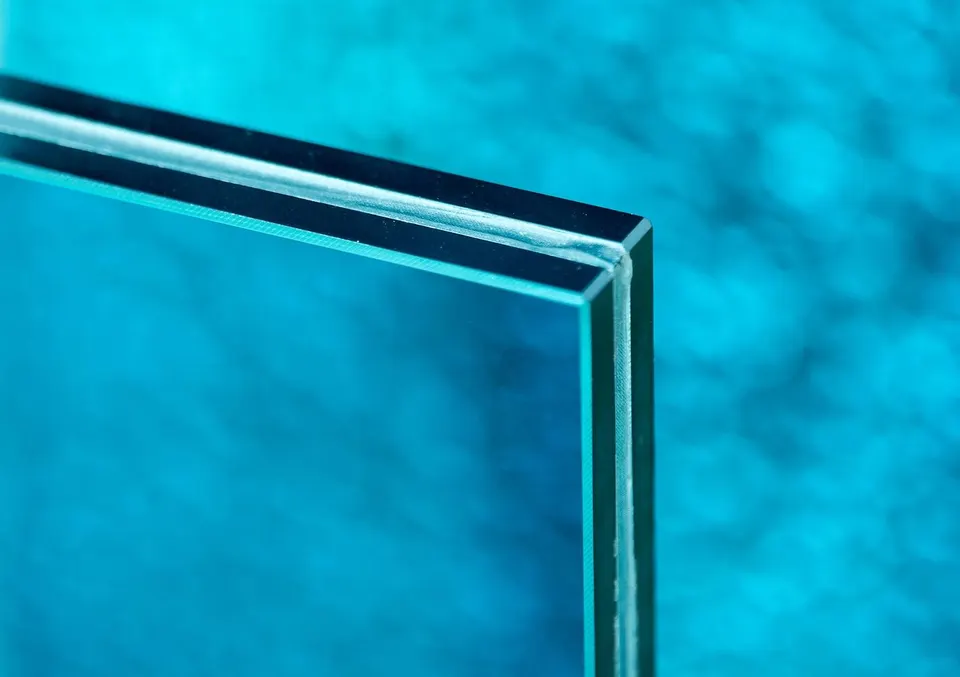

This is a glass wall almost nobody is planning for. Recently, as part of my series interviewing AI-native founders, I sat down with Spiros, founder of the AI-native company Resolve. As he puts it:

“Your first AI crisis won’t be that you built too little. It will be that you can’t safely run what you’ve already shipped.”

Most leaders aren’t seeing this. They’re celebrating adoption of AI, but value only happens when this new software runs reliably. For most organizations, AI will make that harder, not easier.

Most of the attention (and venture dollars) in enterprise AI has focused on building software faster:

That’s important. But it’s only one part of what a software organization does. The other part, the one leaders underestimate, is running that software in production:

In many large enterprises, this “run” side of the house already consumes an army of people. Some companies have thousands of site reliability engineers (SREs) and operations staff dedicated to keeping the lights on.

If AI helps your teams build faster, you will naturally end up with more applications, more complexity, more moving parts. Successfully delivering new software with AI magnifies the stress on your operations that’s already stretched thin.

Most leaders are celebrating adoption of AI, without looking around the corner at the second-order consequences.

So why hasn’t AI solved the run side the way it’s solving the build side? Running software in production has always been hard. Systems are fragmented. There is no single pane of glass for operating enterprise-scale applications in production.

You need to reason across everything at once:

Even the expertise to reason across these systems is siloed. Production incidents don’t respect org charts. The answer often requires context from multiple teams, but no single person has the full picture. Often, no single team does either.

Lastly, knowledge is often undocumented. The patterns that matter most live in the heads of senior engineers who’ve seen it before. It’s not documented.

This is why running production is a hard problem – both for humans or AI.

That’s a very different category of problem than using general purpose models or sprinkling AI on top of existing tools. It requires deep domain expertise in running production and advanced AI agents capable of operating safely in the most sensitive parts of the stack.

As Spiros put it to me, models alone don’t solve this: “You’re outside the training set of generic AI. You need agents that understand your code, your infra, your telemetry, together; and can act with confidence in live production.”

Right now, most enterprises simply throw more people at the problem:

This is unsustainable. And as AI accelerates the pace of change, it becomes an even bigger drag on speed, innovation, and cost.

If this problem is so big, why isn’t it already a top five priority for CIOs and CEOs?

Because it’s invisible at the wrong altitude. Today, the pain is felt deepest by:

Meanwhile, the C-suite is focused on:

Here’s the disconnect: We’ve defined AI productivity as output: code written, features shipped, applications deployed. By that measure, AI adoption seems to be working.

But output is not outcome. Productivity isn’t how fast you create. It’s how much value you deliver sustainably: the ability to ship and run, without the system collapsing under its own weight.

By that measure, most AI investments are making organizations less productive. You’re 10x faster at creating complexity.

Whereas the operations crisis is often seen as a concern something two levels down will “handle”. It isn’t framed as what it actually is: a strategic constraint on the company’s ability to compete in an AI-first world.

You can, however, make this a top priority by clearly naming the glass wall they’re about to hit:

“You’re pushing hard to adopt AI. The biggest thing that may bite you isn’t whether those projects work, it’s that your teams won’t be able to run the resulting complexity without breaking.”

In sales, you sell more aspirins than vitamins. This isn’t a “nice to have future capability.” It’s an aspirin for a very real headache: the operational load that will come with AI success.

If you’re serious about becoming AI-first as an engineering leader, don’t just ask “How do we use more AI?”

Start asking:

Here’s how I’d advise leadership teams to respond:

In this AI-native series, my goal is simple: to surface what founders who live at the bleeding edge see that traditional enterprises often miss. With Reindeer, we’ve seen how AI-native platforms are beginning to rewire how work itself gets orchestrated. And with Notch, we’ve examined how core workflows and systems integration are being rebuilt for an agent-driven world.

With founders like Spiros at Resolve, we’re learning something very important: The risk of AI isn’t just failing to adopt it fast enough. The real risk is succeeding and then being crushed by the complexity you’ve created.

If you’re a CEO, CIO, or board member who thinks your AI roadmap is on track because you have more pilots and applications than ever, I’d challenge you:

Don’t just celebrate your first-level success. Look around the corner.

Ask whether your organization is prepared for the operational wave that’s coming with it. Or whether you’re building your own glass wall. The leaders who start solving for that now will be the ones who truly earn the right to call themselves AI-first.

This was originally published on Forbes